An Indigenous wellbeing guide for housing providers

Dr Guy Penny (Tāmaki Makaurau; Ngāti Kahungunu ki Te Wairoa) and Dr Lori Leigh from the New Zealand Centre for Sustainable Cities at the University of Otago discuss their recently published guide for housing providers. This guide offers a learning and development tool for supporting the wellbeing of Māori tenants based on the Whakawhanaungatanga Māori Wellbeing Model.

"Ka hanga whare te tangata, ka hanga tangata te whare"

The people build the house and the house builds the people

This whakataukī, a traditional poetic expression of wisdom for Māori, the indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand (AoNZ), forms the opening of Māori Wellbeing: A Guide for Housing Providers (the Guide), a newly published learning and development tool for practical application in the housing sector.

Broadly, the whakataukī emphasises the reciprocal relationship between people and their environment. More specifically, it highlights the home as a fundamental pillar of wellbeing. Indeed, where we live, and the houses we live in, have a major influence on our wellbeing both over the long-term and short-term. It also speaks to collective action and pro-action––the idea that, if a home can no longer support wellbeing, another must be built.

In this article, we discuss the need for a culturally-led approach in the provision of public housing, and report on a recently published guide designed to encourage and support public housing providers to develop the organisational capabilities to better meet the wellbeing needs of their Māori tenants.

Wellbeing and culturally-led housing

All people have common wellbeing needs, yet wellbeing is shaped by individual and group characteristics, with culture being a key factor. Indeed, there is widespread recognition and evidence within public health systems globally that culturally-led approaches to wellbeing are the most effective (Rice, Z.S., Liamputtong, P., 2023).

As part of urban infrastructure that helps optimise wellbeing, housing plays an important role––perhaps the most important role––particularly as home is where people spend most of their time. Housing that meets the many different needs of occupants is critical if wellbeing is to be optimised. Affordability, dwelling quality, layout and location, the neighbourhood, connections with nature, access to the right services and amenities, and social and employment networks all play a part in the wellbeing of those being housed.

Housing tenure also plays a critical role in the wellbeing of whānau (families), whether one owns a home or is renting has implications for wellbeing. Renting, regardless of if it’s in the private or public housing market, introduces a landlord-tenant relationship that can have both positive and negative impacts on tenant wellbeing. Renters have significantly less autonomy than homeowners in decisions about where they live and the house they live, resulting in less control over factors that impact their wellbeing. This is further exacebated through cultural differences between tenants and the model of housing provision they are subject to.

"Māori make up a significant proportion of public housing tenants, and increasingly, Māori whānau are renting in the private market rather than purchasing their own homes."

Housing that is located, arranged and designed to meet the needs of Indigenous peoples is an important consideration for public housing providers in Aotearoa New Zealand (AoNZ), all of which have limited budgets and a plethora of other pressing considerations. Growing evidence that culturally-led approaches to wellbeing are the most effective has permeated the way researchers within the New Zealand Centre for Sustainable Cities at the University of Otago think about public housing provision in AoNZ. We asked ourselves:

What would it take to move to a more culturally-led public-housing model in AoNZ? What support do public housing providers need to do this?

Public housing and wellbeing

In AoNZ, public housing is government-subsidised rental accommodation for people who can't afford to live in a private rental. These houses may be run by a Community Housing Provider (CHP) or by Kāinga Ora––Homes and Communities (the New Zealand Crown agency that manages public housing and develops urban areas).

Since 2018, the number of CHPs and the homes they operate has nearly doubled. There are now 92 CHPs with around 18,500 homes, housing 35,000 people. Kāinga Ora–Homes and Communities operates around 72,000 homes across the country, housing around 185,000 people, and is by far the largest public housing provider in NZ, five times larger than all the CHPs combined. Collectively, public housing supports around 220,000 people, with Māori making up 39% of tenants, Pakeha/European 27%, Pacific Peoples 26% and other non-Europeans around 8%.

"92 CHPs are not subject to these same governance rules, nor do they need to provide culturally specific governance, tenancy or property services and management, or uphold the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi."

Given Kāinga Ora is an agent of the Crown, its Board must ensure the organisation has the capability and capacity to uphold the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) and its principles, to understand and apply Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993, and to engage with Māori and to understand Māori perspectives (Kāinga Ora––Homes and Communities Act, 2019). However, the 92 CHPs are not subject to these same governance rules, nor do they need to provide culturally specific governance, tenancy or property services and management, or uphold the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, despite Māori making up over a third of public housing tenants.

Like Kāinga Ora, CHPs are subject to raft of regulations, some of which have indirect wellbeing effects, including building performance standards and RTA (landlord obligations). However, there is no mechanism or requirement for CHPs to formally assess the health and wellbeing of tenants with respect to property or tenancy services.

Under the CHP performance standards (CHRA, 2024), CHPs

should consider the location, size, and access to amenities of their property portfolio and whether it is appropriate for their target cohort (p22). Futhermore, CHPs must have policies that guide their management decisions to ensure the outcomes for tenants are appropriate, measurable, and monitored (p11), but only in relation to affordability, access to information, and access to services (including a complaints process)––not specifically health and wellbeing.

In our consultation with CHPs, many spoke about their commitment to tenant wellbeing and to uphold and honour Te Tiriti, despite there being no regulatory requirement to do so. Indeed, it was CHPs who signalled the need for support. They believed that explicitly recognising and supporting Māori wellbeing is of critical importance if individuals, whānau, communities and neighbourhoods are to thrive.

To their credit, they acknowledged they needed help to more fully understand Māori wellbeing in the context of housing, and to develop and deliver housing services that better support and improve the wellbeing of their Māori tenants. Hence, we set about creating Māori Wellbeing: A Guide for Housing Providers.

The Whakawhanaungatanga Māori Wellbeing Model

The idea for a guide arose from discussions with public housing providers involved in the Public Housing and Urban Regeneration: Maximising Wellbeing Research Programme (PHUR) (NZ Centre for Sustainable Cities, 2024) after the publication of the paper A Whakawhanaungatanga Māori Wellbeing Model for Housing and Urban Environments (Penny et al., 2024).

The PHUR Research Programme is a collaboration between researchers and seven public housing organisations (Kāinga Ora––Homes and Communities, plus six CHPs). The aim of the research programme was to improve the wellbeing of public housing tenants by providing evidence that leads to healthier and more environmentally sustainable development (NZ Centre for Sustainable Cities, 2024). Research foci (focus) included transport, energy, housing quality, governance, wellbeing, community formation and urban design, and Te Ao Māori (the Māori World).

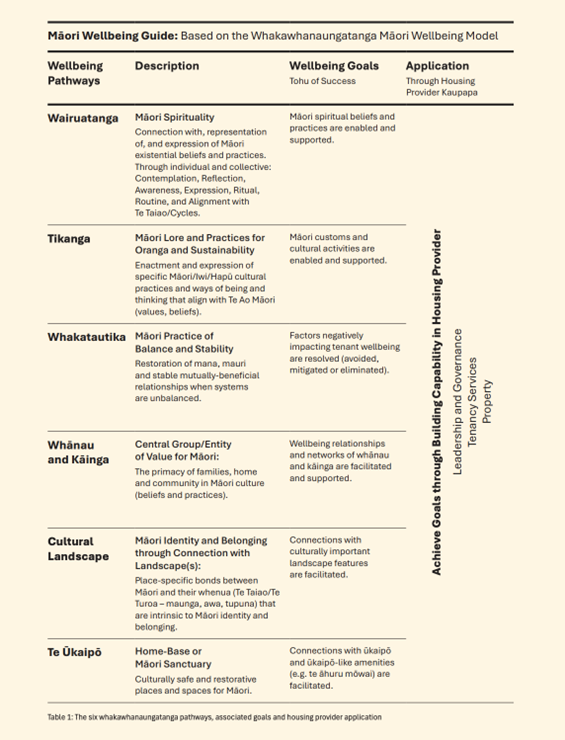

The Whakawhanaungatanga Māori Wellbeing Model, developed by Māori researchers for the programme and partner organisations, centres on the concept and practice of whakawhanaungatanga (making and strengthening connections and relationships). The model presents six pathways, drawn from Te Ao Māori, through which wellbeing is enhanced using whakawhanaungatanga: wairuatanga, tikanga, whaukatautika, whānau and kāinga, cultural landscapes, and te ūkaipō.

The figure below, taken from our Guide, provides further explanations of the

whakawhanaungatanga pathways:

Upon introduction to the Whakawhanaungatanga Māori Wellbeing Model, housing providers expressed an interest in an evaluation tool using a set of indicators based on the pathways. They emphasised that they wanted a practical way to self-assess the extent to which their organisations were meeting the wellbeing needs of their Māori tenants, and to identify gaps in their understanding and practice.

Furthermore, they were interested in guidance and resources to improve and develop organisational capabilities across Governance, Tenancy Services and Property so these functions more effectively aligned with the wellbeing needs of their tenants.

Māori Wellbeing: A Guide for Housing Providers

In response to these signals from public housing providers, we embarked on a journey to turn our research into practice. Following approval of a project plan by PHUR directors, we undertook a scoping review of evaluation and assessment frameworks and guides––primarily in the health, environmental and urban sectors. This exposed us to a range of different methods, approaches and design elements used in evaluation and assessment tools.

The Guide was then advanced with input from an advisory group with expertise in kaupapa Māori research, public health, housing and urban design. Most importantly, it was developed with support and feedback from Community Housing Aotearoa (the peak body for New Zealand’s community housing sector) and iterations of the Guide were tested with community housing providers and a Māori tenant focus group.

Māori Wellbeing: A Guide for Housing Providers is divided into three parts:

Part One provides the contextual basis for the guide, describes its process of creation, and discusses the model and values that underpin the guide, including Te Tiriti O Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi).

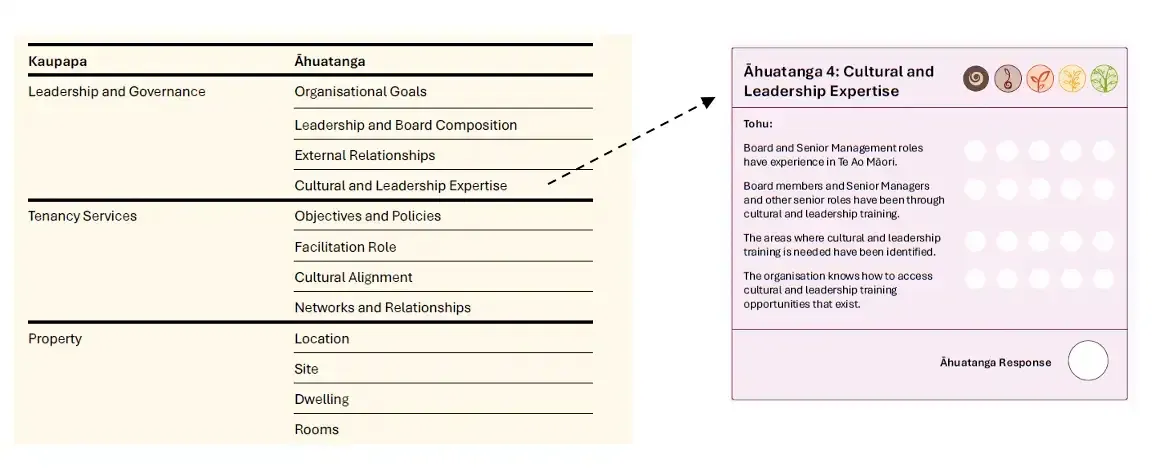

Part Two centres on the learning and development process. In teams or as individuals, users of the Guide work through a set of assessment and reflection tasks associated with their current organisational capabilities in three functional areas (Kaupapa)––Leadership and Governance, Tenancy Services and Property––each of which is broken down into four sub-areas or attributes (Āhuatanga). Each Āhuatanga has four indicators (Tohu).

See example below taken from the Guide:

In groups or individually, Guide users subjectively rate their performance for each tohu using our tree-growth stage rating icons before aggregating scores within each Āhuatanga and Kaupapa. Based on the results of the self-assessement, users of the Guide then select activities and resources that form the basis of an Action Plan for Building Māori Wellbeing Capability––either for individuals, for their team or across the organisation.

Part Three of the Guide provides the user with a list of resources and references to assist them as they work through the guide and create their wellbeing plan.

While designed primarily for housing providers, the Guide offers ideas to organisations operating in the housing, neighbourhood and urban development sector interested in Māori wellbeing, and to those organisations wanting to develop or enhance their capability to support the wellbeing of Māori.

We launched Māori Wellbeing: A Guide for Housing Providers in November 2024 at the Community Housing Aotearoa Conference in Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland AoNZ, and are offering a series of workshops that support the Guide’s content. We are continuing to work with public housing providers and seek their feedback on how the application of the Guide is progressing in their organisations.

Māori Wellbeing: A Guide for Housing Providers is available in hardcopy to order, spiral-bound to enhance its usability, and the worksheets can be photocopied. It is also available for digital download.

References

Community Housing Regulatory Authority (2024). Performance Standards and Guidelines––

https://www.chra.hud.govt.nz/

Kainga Ora - Homes and Communities Act, 2019 https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2019/0050/latest/LMS169206.html

NZ Centre for Sustainable Cities (2024). https://www.sustainablecities.org.nz/our-research/current-research/public-housing-urban-regeneration-programme

Penny, G., Logan, A., Olin, C. V., O’Sullivan, K. C., Robson, B., Pehi, T., … Howden-Chapman, P. (2024). A Whakawhanaungatanga Māori wellbeing model for housing and urban environments. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 19(2), 105–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2023.2293988

Rice, Z.S., Liamputtong, P. (2023). Cultural Determinants of Health, Cross-Cultural Research and Global Public Health. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health. Springer, Cham.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96778-9_44-1

Other articles you may like

We acknowledge the Wathaurong, Yuin, Gulidjan, and Whadjuk people as the traditional owners of the land where our team work flexibly from their homes and office spaces. Ahi Australia recognises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first inhabitants of Australia and the traditional custodians of the lands where we live, learn and work. Ahi New Zealand acknowledges Māori as tangata whenua and Treaty of Waitangi partners in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Copyright © 2023 Australasian Housing Institute

site by mulcahymarketing.com.au