FOUR DECADES OF ESTATE RENEWAL IN NSW: From people to profit, and then…?

Dr David Lilley from UNSW Cities Institute was pleased to see the NSW Labor Government announce billions of dollars for social housing in the 2024 Budget, but he questions whether this is the beginning of transformational change, or merely another round of reform.

We have entered an unusual era in NSW and Australian housing policy.

Only a decade or so ago, it seemed impossible for social housing to compete with health, education and other areas of public policy for community or political attention. Today, the community at large is highly sensitised to the housing affordability crisis, and politicians from across the political spectrum increasingly recognise the need for action.

We need to think carefully about what we do with this opportunity, which I will consider through the lens of social housing estates.

The history of estates

From its earliest days, the NSW Housing Commission tended to cluster public housing on large parcels of land. While this was a matter of both convenience and cost minimisation, in many cases, it was also because public housing was being used to catalyse regional development, which required a critical mass of new residents in newly developed areas. This demonstrates that the objectives and rationale of social housing supply have always been pragmatic - or less than pure, depending upon your perspective.

According to Housing NSW (2002), there were four distinct periods of estate development in NSW. Estates built in the 1940s and 1950s were known as ‘neighbourhood estates’ because “these were not just homes, but whole communities complete with amenities such as schools, hospitals and shops” (p. 17). Examples of neighbourhood estates located in Sydney include those located in Maroubra and Dundas Valley.

"Doubts had begun to emerge regarding the development of large-scale estates by the 1970s."

The 1960s saw the development of the ‘great estates and high-rises’, developed on Sydney’s urban fringe and in the inner city respectively. The great estates included 6,000 dwellings in southwest Sydney’s Green Valley, and 8,000 dwellings in western Sydney’s Mount Druitt. In both cases, numerous new suburbs were formed.

Doubts had begun to emerge regarding the development of large-scale estates by the 1970s, with Green Valley and Mount Druitt beginning to be seen as “ghettos of disadvantaged people” (p. 21). These concerns notwithstanding, the Housing Commission persisted with the development of broadacre estates in Sydney’s west and southwest. Being smaller than the Green Valley and Mount Druitt estates, and being clustered around rail corridors, they were known as the ‘corridor estates’.

The last estates developed in NSW were built in the 1980s and were known as ‘micro estates’. They typically involved the replacement of small clusters of old freestanding fibro houses with higher density housing.

Responding to estates

By the 1990s, attention shifted from building estates to responding to the issues that were, or were perceived to be, associated with them. These included low quality construction and poor maintenance, along with high rates of crime, unemployment, ill-health, school failure, anti-social behaviour, drug use, welfare dependence, stigma and social isolation (Woodward, 1997; Housing NSW, 2002; Lilley, 2005).

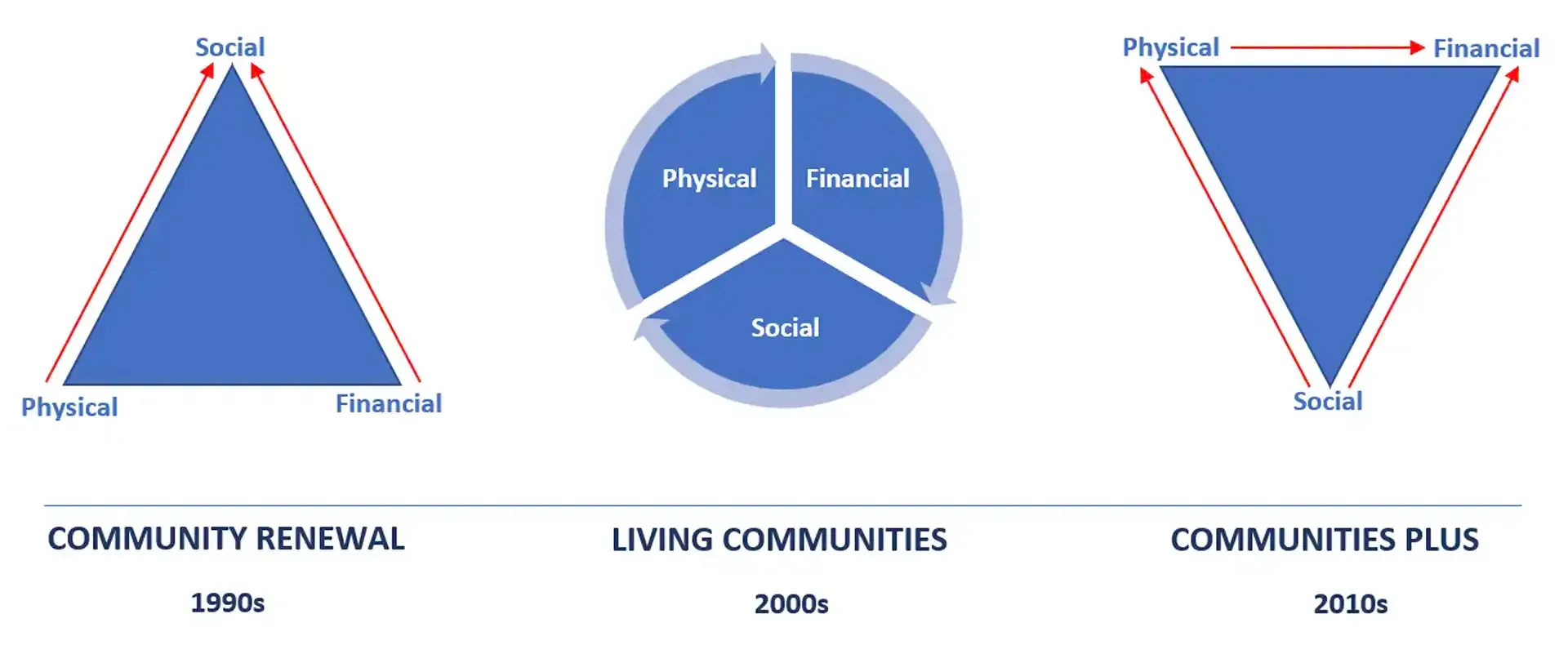

Approaches to estate renewal in the 1990s had a primarily social orientation, with community participation, human service initiatives, and housing and neighbourhood upgrades used to improve social outcomes, consistent with traditional notions of social citizenship and the welfare state. This included both the Neighbourhood Improvement Program (NSW Department of Housing, 1996) and two iterations of policy (NSW Department of Housing, 1999, 2001), each of which relied on considerable public expenditure.

"The improvement of social outcomes was retained as an objective but was ‘balanced’ against financial and urban planning considerations."

When a new approach was designed to guide the redevelopment of the Bonnyrigg Estate in the mid-2000s - known as the Living Communities approach (Coates and Shepherd, 2005) - the improvement of social outcomes was retained as an objective but was ‘balanced’ against financial and urban planning considerations. The housing authority ceded control of the project to a private sector consortium under a comprehensive public private partnership (PPP) contract. This was an attempt to utilise a market approach for social ends consistent with so-called ‘Third Way’ politics, which had recently been popularised by the Blair Government in the UK (Giddens, 1998).

The mid-2010s saw a major shift in both the means and ends of estate redevelopment. A report by the NSW Audit Office (2013) made clear that the social housing ‘business model’ was not working, as the rents collected from tenants were insufficient to cover the housing authority’s general operations, let alone increase the volume of social housing. The Director General at the time observed that:

In public housing there’s one big lever to pull - the potential to more actively redevelop higher value land under the portfolio to provide ongoing returns to reinvest in social housing. This would take time to achieve but is promising (Coutts-Trotter, 2013).

This led to the launch of the Communities Plus approach (NSW Family and Community Services, 2016; NSW Land and Housing Corporation, 2017, 2018), which inverted the original hierarchy of means and ends. Redevelopment would now be conducted to maximise housing density and financial return, and tenant consultation and social service provision became a means of assuaging tenants, while a stream of funding with which to subsidise the operation of the social housing portfolio was pursued. This constituted an instrumentalist approach, consistent with market fundamentalism or neo-liberalism (Lilley, 2024). Each of these three phases of renewal is depicted in figure 1 .

For more than a decade now, the housing authority’s primary focus has been on redeveloping social housing estates in partnership with the private sector, for the purpose of generating funds to maintain and grow the social housing portfolio in the absence of Treasury appropriations. This does not preclude social benefits, but they are not the main game, as illustrated by two quotes regarding the redevelopment of Waterloo South, a redevelopment project announced at the beginning of the Communities Plus era.

Consider first the reflections of a staff member from the NSW housing authority:

So, Waterloo, if it's getting done, it's getting done because there's enough density there and enough private sales to pay for the replacement of housing. That's sort of the bottom line. And the fact that it's generating some social benefits is almost accidental. (Lilley, 2024, p. 149)

Nearly 10 years after the project was announced, numerous masterplans have been developed, multiple financial feasibility studies have been conducted, a tender process has been run to select a private sector consortium to run the project, and the signing of contracts is said to be imminent. However, no Social Impact Assessment (SIA) has been conducted. A Health Impact Assessment (HIA) conducted externally was watered down and subsequently buried, and social considerations have been largely sidelined (REDWatch, 2022; Lilley, 2024). While an SIA will be conducted when a Development Application (DA) is lodged, the core elements of the project will already be fixed, based on financial, urban planning and contract considerations. As one local resident has put it:

The stated purpose has always been to provide new, better public housing… The stated purpose is false… The only reason [for the project] is they can make money out of doing it. So, to hell with the disruption to the people who live in the buildings. And, you know, it’s a huge disruption. (Lilley, 2024, p. 153)

The current approach

At a meeting regarding Waterloo on 5th June 2023, the NSW Minister for Housing, The Hon. Rose Jackson, MLC, made three bold claims:

First, “the interest that the Labor Government has shown in delivering social and affordable housing is an incredibly refreshing change from the approach of the previous government, which didn't even have a housing minister in the Cabinet and showed no interest”.

Second, the Labor Government won’t sell government land as part of estate redevelopment projects.

Third, the Labor Government will re-activate the Compact for Renewal (Shelter NSW, Tenants’ Union of NSW and City Futures Research Centre UNSW, 2017), which is “a really good document that talks about delivering control and autonomy and agency and voice”. (Jackson, 2023)

A month after this meeting there was an announcement that the proportion of social and affordable housing in Waterloo South would be increased from 34 per cent to 50 per cent, resulting in approximately 500 additional social and affordable homes. And the following year, the NSW Budget included A$5.1 billion over four years to deliver 6,200 new social homes and 2,200 replacement social homes across NSW.

This change is very welcome, but we do need to put it in context.

The nature of change

The management theorist and consultant Russell Ackoff (2004) makes an important distinction between reforming and transforming public policy and administration. Reform is concerned with improving the instruments used to pursue policy objectives, while transformation is concerned with changing the purpose of the policy in question, along with the redesign of related administrative systems.

"Reform is concerned with improving the instruments used to pursue policy objectives, while transformation [changes] the purpose of the policy."

When the rationale and outcomes of the great estates and high-rises were being called into question, the practice of building estates was reformed. That is, the same basic approach was used to develop the corridor estates, followed by the micro estates, but it was progressively reduced in scale.

In contrast, the shifts in estate policy from the 1990s to the 2010s were much more fundamental. Earlier initiatives were intended to improve life for residents and required significant public expenditure, while later approaches were intended to raise funds with which to subsidise the operation of the social housing system, in the absence of substantial recurrent funding. This constituted transformational change.

Where to now?

Since the Minns Labor Government came to power in 2023, a number of very welcome changes to social housing funding, policy and practice have been made.

However, these have not set a fundamentally different path from the one they inherited, at least not yet. Despite promises to the contrary, half of the land in sites such as Waterloo South will still be lost to the private market when they are redeveloped.

Additionally, while the funding announced in the 2024 Budget was substantial, it only covers the upfront delivery of social housing supply over the short to medium. It doesn’t change the social housing ‘business model’. Rents still don’t cover costs, and redevelopment will still be required to make up the shortfall, unless more substantive changes are made.

None of what has been said above is intended to detract from the work the Minns Labor Government has begun in the social housing portfolio. Rather, it is to point out he Government now needs to make a decision about which road it wants to go down.

Are its efforts the beginning of transformational change, or will it stop at reform?

References

Ackoff, R. (2004) ‘Transforming The Systems Movement’, The Systems Thinker, 15(8), pp. 2–5.

Coates, B. and Shepherd, M. (2005) ‘Bonnyrigg Living Communities Project: A Case Study in Social Housing Public Private Partnerships’, in. National Housing Conference, Perth, Western Australia.

Coutts-Trotter, M. (2013) ‘Director General: Public Housing Challenges’, Inner Sydney Voice, Winter(119), p. 20.

Giddens, A. (1998) The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Housing NSW (2002) ‘Celebrating 60 Years of Homes for the People’. NSW Department of Housing.

Jackson, R. (2023) ‘Comments by NSW Housing Minister Rose Jackson’. REDWatch Meeting, Alexandria Town Hall, Sydney, 5 June. Available at: http://www.redwatch.org.au/RWA/Waterloo/lahc22-23/070605rj (Accessed: 23 June 2023).

Lilley, D. (2005) ‘Evaluating the “Community Renewal” Response to Social Exclusion on Public Housing Estates’, Australian Planner, 42(2), pp. 59–65.

Lilley, D. (2024) People or Profit: The use of critical systems thinking to diagnose and transform housing policy for health, wellbeing, and equity. UNSW. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/1959.4/103259.

NSW Auditor General (2013) Making The Best Use of Public Housing: New South Wales Auditor-General’s Report to Parliament. Sydney: Audit Office of New South Wales.

NSW Department of Housing (1996) ‘Creating Vital, Viable Communities: The Public Housing Neighbourhood Improvement Program’.

NSW Department of Housing (1999) ‘Community Renewal: Building Partnerships - Transforming Estates Into Communities’.

NSW Department of Housing (2001) ‘Community Renewal: Transforming Estates Into Communities - Partnerships & Participation’. NSW Department of Housing.

NSW Family and Community Services (2016) ‘Future Directions for Social Housing in NSW’. NSW Government.

NSW Land and Housing Corporation (2017) ‘Communities Plus’. NSW Government. Available at: www.communitiesplus.com.au (Accessed: 10 May 2019).

NSW Land and Housing Corporation (2018) ‘Communities Plus Industry Briefing’. NSW Government. Available at: www.communitiesplus.com.au (Accessed: 10 May 2019).

REDWatch (2022) ‘Waterloo South Planning Proposal: Submission 1701’. Available at: https://pp.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/ppr/post-exhibition/waterloo-estate-south (Accessed: 30 June 2022).

Shelter NSW, Tenants’ Union of NSW and City Futures Research Centre UNSW (2017) A Compact for Renewal: What tenants want from Renewal. Available at: https://shelternsw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2017-A-compact-for-renewal-what-tenants-want-from-renewal-2017.pdf (Accessed: 13 June 2023).

Woodward, R. (1997) ‘Paradise Lost: Reflections on Some Failings of Radburn’, Australian Planner, 34(1), pp. 25–29.

Other articles you may like

We acknowledge the Wathaurong, Yuin, Gulidjan, and Whadjuk people as the traditional owners of the land where our team work flexibly from their homes and office spaces. Ahi Australia recognises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first inhabitants of Australia and the traditional custodians of the lands where we live, learn and work. Ahi New Zealand acknowledges Māori as tangata whenua and Treaty of Waitangi partners in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Copyright © 2023 Australasian Housing Institute

site by mulcahymarketing.com.au