Andy Marlow - architect, passivhaus designer and director at Envirotecture and Passivhaus Design & Construct - zeros in on how quality in housing construction can immediately address supply problems, as well as broader positive impacts.

The housing debate in Australia remains a BBQ-stopper with no signs of fundamental change. As an architect, I have spent more hours than I’d like to admit pondering the root causes of the issues with the obvious (in my head) goal of trying to ‘fix’it.

This article pieces together how I see the issues and their interconnections, as well as pointing to potential solutions.

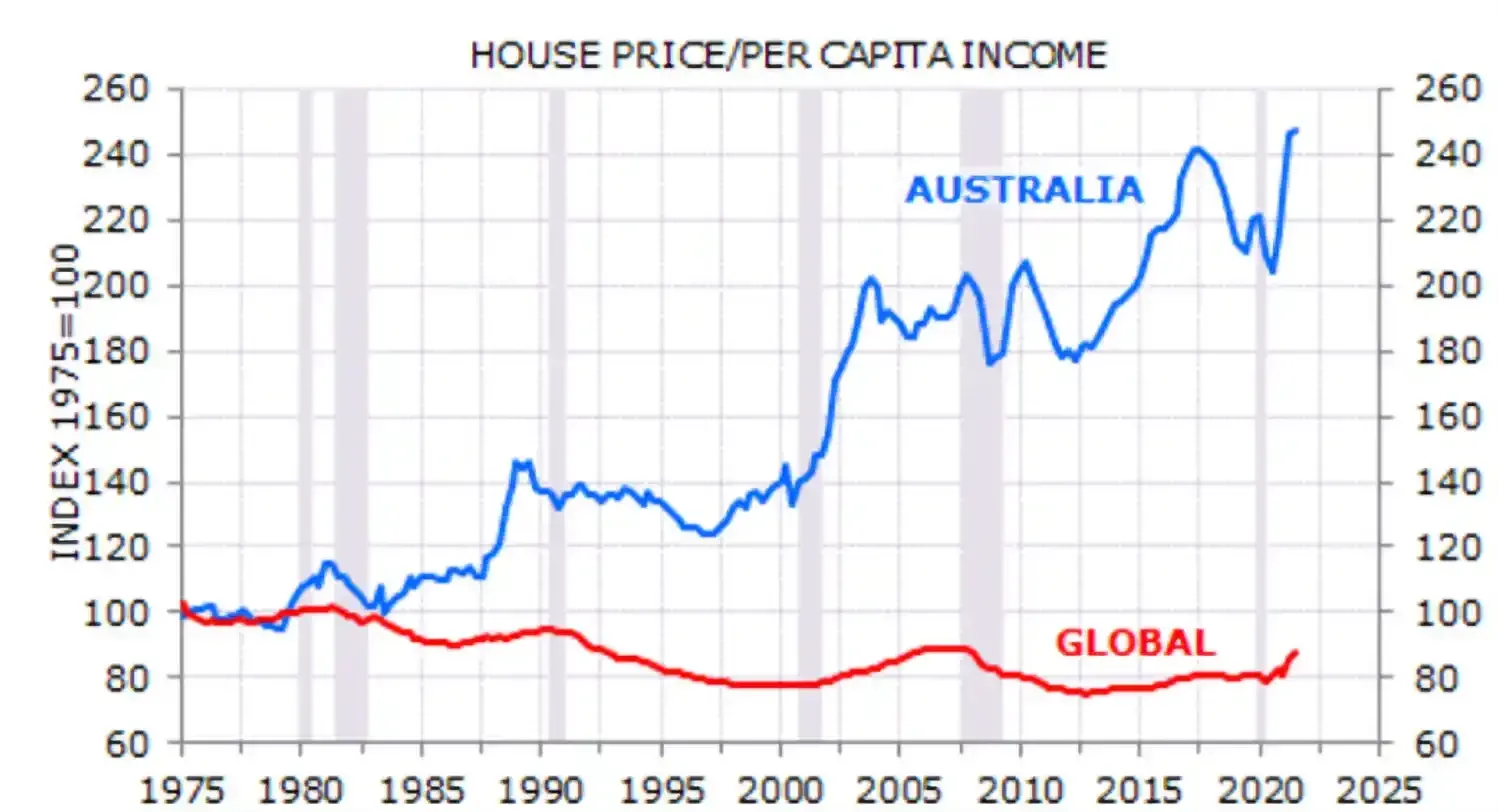

Over my lifetime, the cost of housing in Australia has more than doubled and, while I may have benefited in some ways, it is definitely not a ‘rising house prices are good for my personal wealth’ story. I have come fairly late to this party so, like many, I am burdened with a mortgage that is only viable due to two well-paying professional jobs.

Economists will tell us that the cost of housing, or any ‘product’, results from its input costs. The graphic below shows, on the left-hand side, the theoretical equation for how land is priced. Yet, in reality, the cost of housing comes from the cost of land rather than the other way around.

It is not news that the cost of land is the biggest driver of housing costs. It is why innovative housing models, such as Nightingale - and the small scale, high quality developers such as HipV Hype - struggle to make projects stack up in Sydney where land costs are significantly higher than their original stomping ground, Melbourne, where land is still not cheap.

"The market delivers housing at the profit margins they require, so the pace reflects the rollercoaster of house prices as it is driven by recouping the land costs they paid."

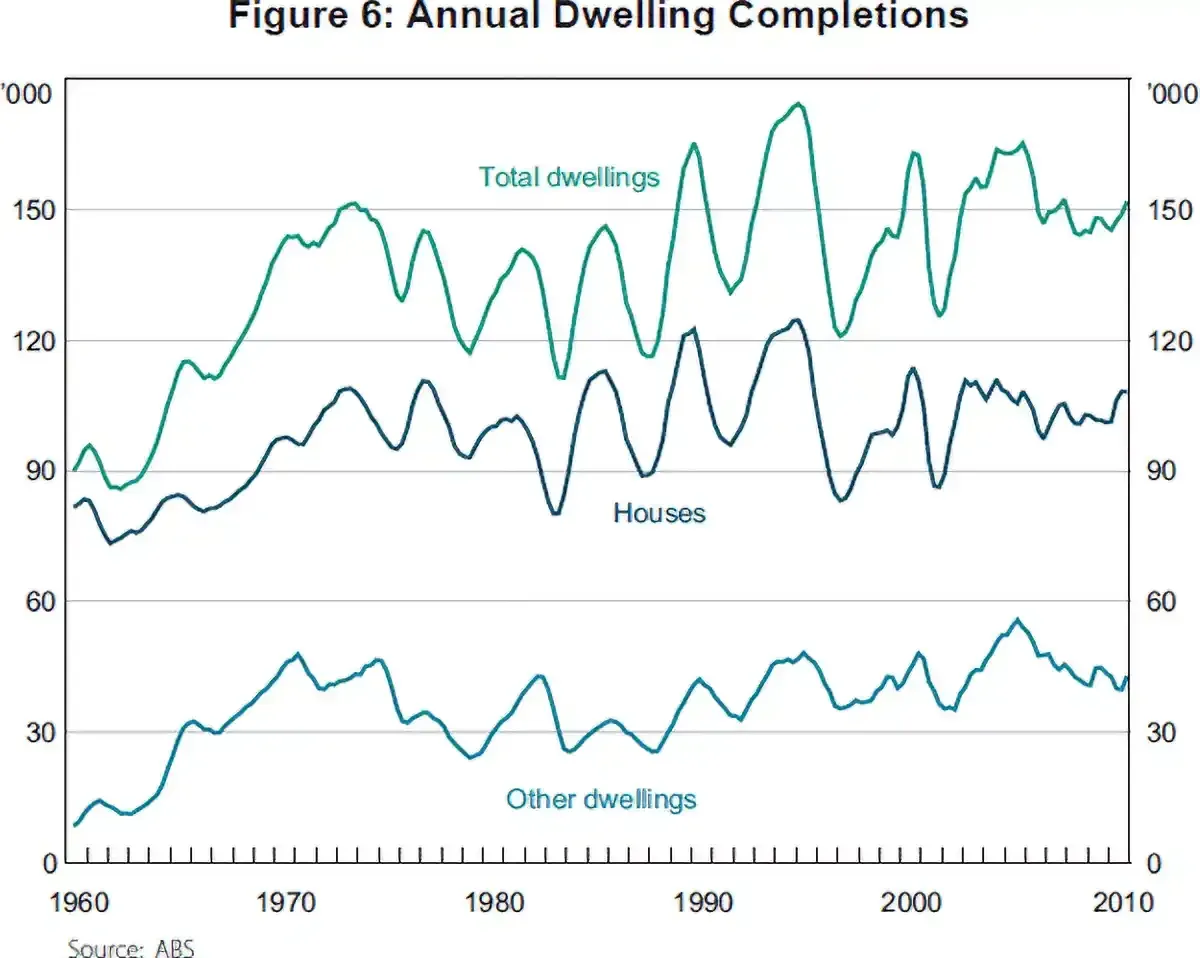

We are continually told the market will save us, that only ‘it’ can deliver the housing we need and that developers can deliver housing cheaper if only the government got out of the way. The reality is the market delivers housing at the profit margins they require, so the pace reflects the rollercoaster of house prices as it is driven by recouping the land costs they paid.

With the price of land beyond the control of any one entity, it is a somewhat sticky situation. This is due to the deep pockets of landholders, many of whom are not developers and are in no hurry or need to sell. History has shown their time will come and that the long-term rewards of doing nothing productive with land gives a great return on investment.

The design and marketing sides of housing development are small pieces of the financial pie, which only leaves construction costs as a controllable variable. This is evidenced by developers attempting to build faster (although not fast enough to allow sell prices to decline) and cheaper.

The video below shows fast construction but far from the current reality of developers.

The project in the video is a certified Passivhaus where the prefabricated walls and roof were assembled in three days. This is a high-quality project with exceptional indoor air-quality, high levels of comfort and very low energy demand.

Given the biggest piece of the financial pie influenced by developers is construction costs, the delivery of cheaply built housing is a sensible reaction to the current market settings. While this may be good for profitability, there are societal costs, not just Opal and Mascot Towers but also the human health impacts and efficiency losses due to low construction standards, whether legal or not.

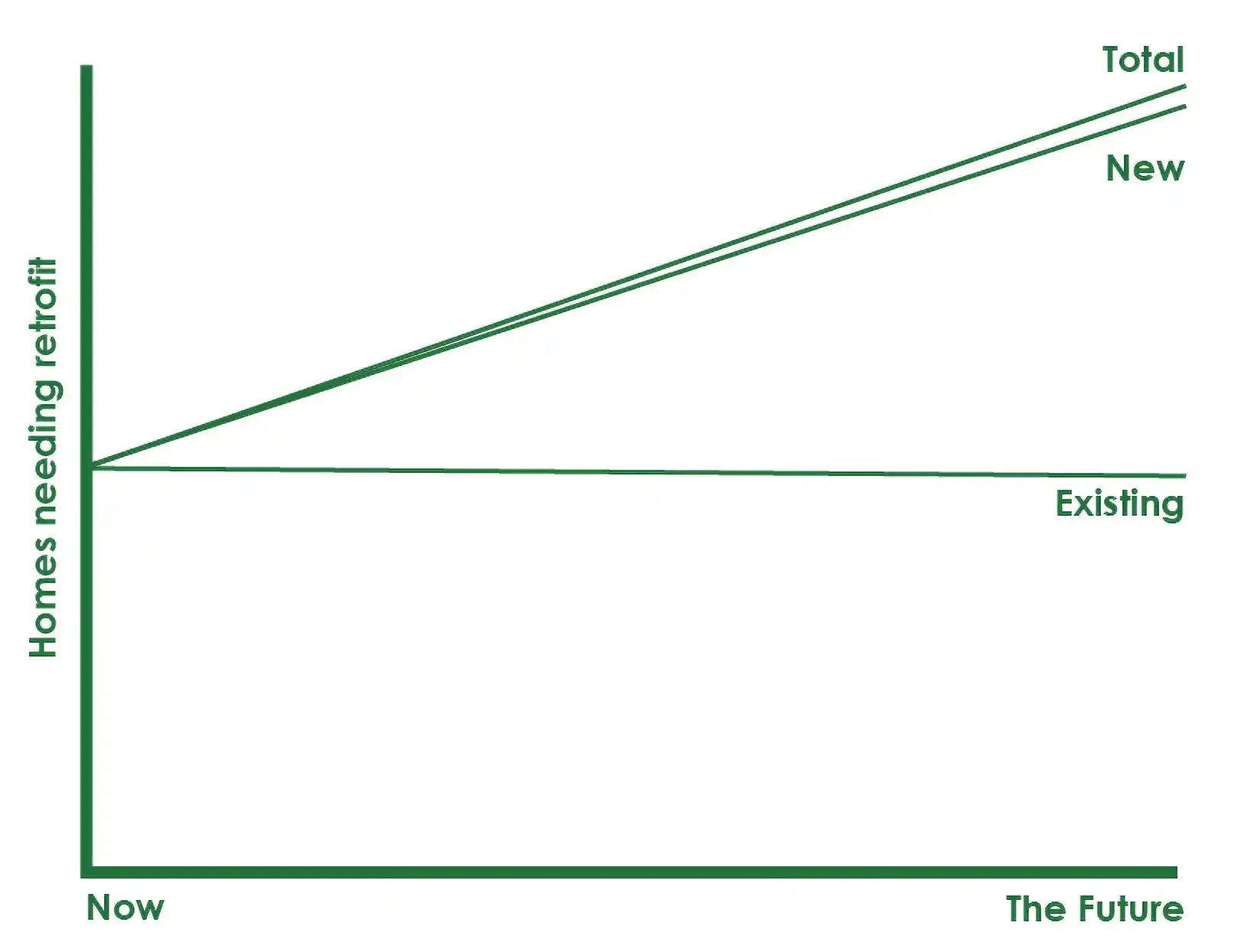

"Considering the scale of the retrofit task already facing us today, adding to it with more, poorly designed, poorly built homes seems to be the ultimate kicking of the can."

The great news for architects and skilled builders is that this current tranche of housing is our future retrofit work. Fixing these buildings, some only five years old, to be fit for occupation in a changing climate does not yet seem to be on the radar for most. Considering the scale of the retrofit task already facing us today, adding to it with more, poorly designed, poorly built homes seems to be the ultimate kicking of the can.

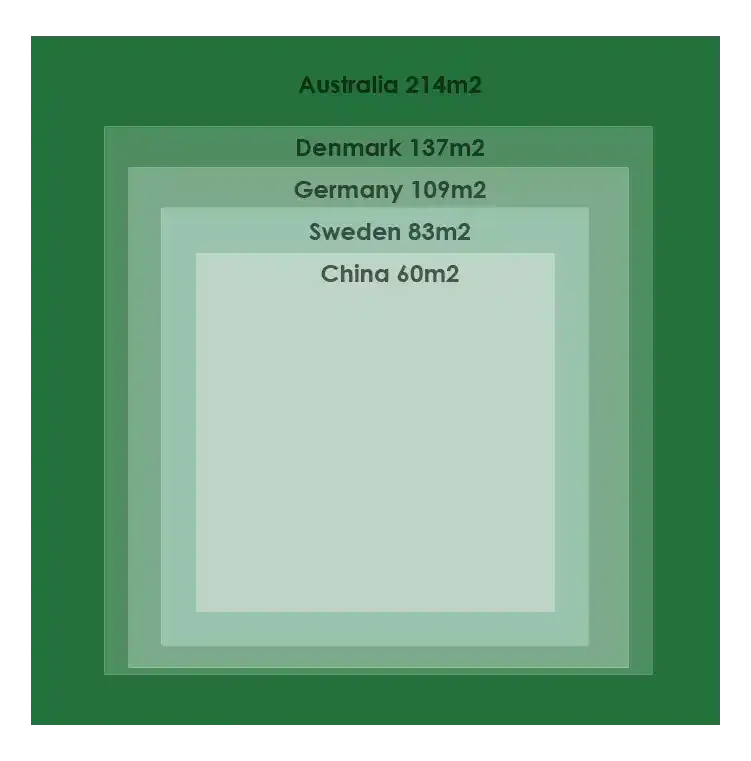

With a continual push to deliver cheaper housing, the politics seem unable to address the ultimate elephant in the room: Size! Australia continues to build the largest homes in the world, although the cost per square metre of many of them is low by global standards. It is safe to say, in almost every case, a smaller, better-designed home could have delivered the same functional outcome, redirecting construction money to build at a higher quality.

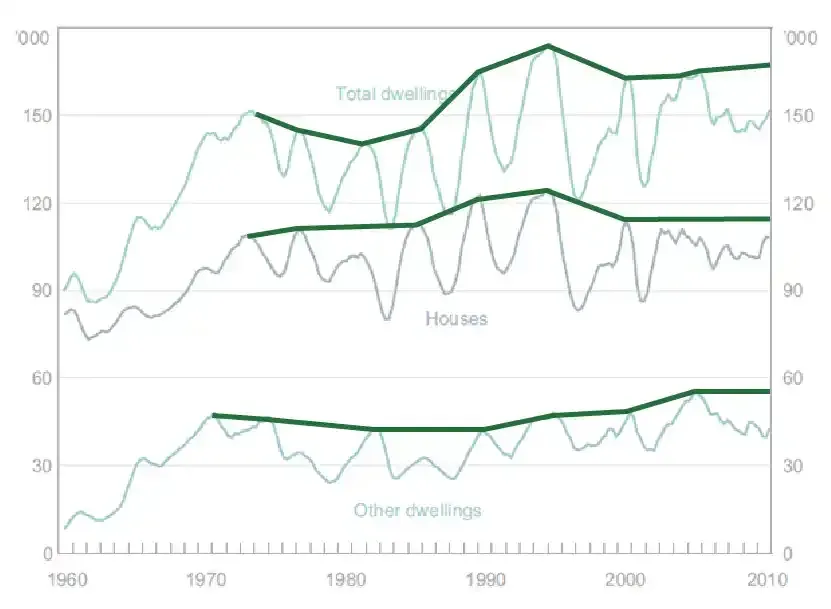

The number of dwellings delivered annually reflects the market forces we've outlined––building and selling to meet profit margin-drivers rather than societal needs. A key impact of this reaches beyond the construction sector to Australian manufacturing. It is estimated that somewhere between 60% to 85% of building materials are imported into Australia each year.

While there are many factors for the decline in Australian manufacturing, the inevitable flow-on effects have come to include long, opaque supply chains, a reliance on global transport networks, and limited innovation in material and product development.

These headwinds have not prevented many from trying, yet the corporate landscape is littered with companies, especially prefabrication ones, who have failed to maintain a viable business. Nearly all these failed stories hark back to inconsistent demand leaving them unable to maintain their infrastructure during slower times. It is hard to compete with a factory, machinery and staff against a bloke, a ute and a dog.

This decline not only impacts on supply chains and innovation but also on the jobs market. The number of well-paying, blue-collar jobs, arguably the driver of Australia's post-war economic boom, has been decreasing for several decades. During this time, Germany has been increasing its share of manufacturing jobs through innovation and product development, with a high-proportion of medium-sized firms often in highly specialised areas. Australia seems to have duopolies in many of its sectors, rather than a diverse tapestry of mid-sized firms.

"Increased running costs reflect not only the increase in electricity prices but also the poor performance of our homes and their increased size."

As the prevalence of well-paying, non-professional jobs decreases and the cost of procuring housing increases, the cost of running homes is rising too. Increased running costs reflect not only the increase in electricity prices but also the poor performance of our homes and their increased size. The current energy-rating system for new homes, NatHERS, uses energy per square metre, whereas homeowners pay for total energy. Bigger homes cost more to run!

For many Australians, the boom in solar PV has almost eliminated running costs. While great news for them, and with positive effects from avoided emissions for wider society, these changes unfairly disadvantage those who don't own their roof––apartment dwellers and renters.

"Eliminating mould from homes would save the health system AUD$2.82billion over the next 20 years."

The reputation of the poor quality of Australian housing extends well beyond high power bills and house prices to peoples' health. Research by Rebecca Bentley and her team at the University of Melbourne found that 27% of Australian homes currently have mould. Eliminating the mould from these homes would save the health system AUD$2.82billion over the next 20 years. These savings would be 1.66 times greater in lower socio-economic groups; the people most negatively impacted by our housing systems and the least able to take meaningful actions for change.

The same research found that household income would increase by AUD$4.21billion over the same 20-year period - a AUD$7billion turnaround.

These productivity benefits and health costs are difficult to quantify, which is why the housing debate rarely tries; it has remained firmly in the energy cost camp. Unfortunately, contrary to popular belief, the cost of energy is not sufficiently high to drive meaningful change. This is not to say that the cost of energy is not a problem for many, just not high enough for real change.

All the aforementioned issues could be addressed by government if the political will existed, yet the rent-seekers, including the 70% of Australians who own homes, make that an unlikely proposition any time soon.

The housing crisis is framed as being about cost, which it is, but it is really a crisis of quality. The creation of larger, poor-quality homes has prevented the nation from using its natural, financial and human resources to create a breadth of functional, right-sized, healthy, comfortable and efficient homes.

Pulling the quality lever is arguably the most palatable and realistic approach as the current state of politics makes addressing the other underlying issues feel like a pipedream––good for headlines but not delivery on the ground.

Resistance to changes to the building code is high! The lobbying groups come out in full force as evidenced by the Housing Industry Association in South Australia recently gaining a commitment to freeze the code for 10 years, with Peter Dutton following hot on their heels at the national level.

Yet other jurisdictions have proposed the opposite. In British Columbia, Canada, a ‘step code’ was introduced in 2017, setting out five steps of code improvements that culminate in net-zero-ready buildings by 2032. Its first step was to prove compliance with the current code - something we are yet to embrace in Australia - and, from there, ramped up the standards. While many projects will have continued to meet the bare minimum each year, many have seen the writing on the wall and leapt straight to Step Five, looking to gain a market-leading advantage by upskilling in advance of the competition.

The Dutton-esque arguments around the Building Code adding to construction costs hold water like a sieve. The evidence shows that, post-handwringing, every code change cost impact prediction is wrong. Industry works out how to deliver the ‘new normal’ with increasing cost-efficiency every time; a testament to Australia innovation and adaptation.

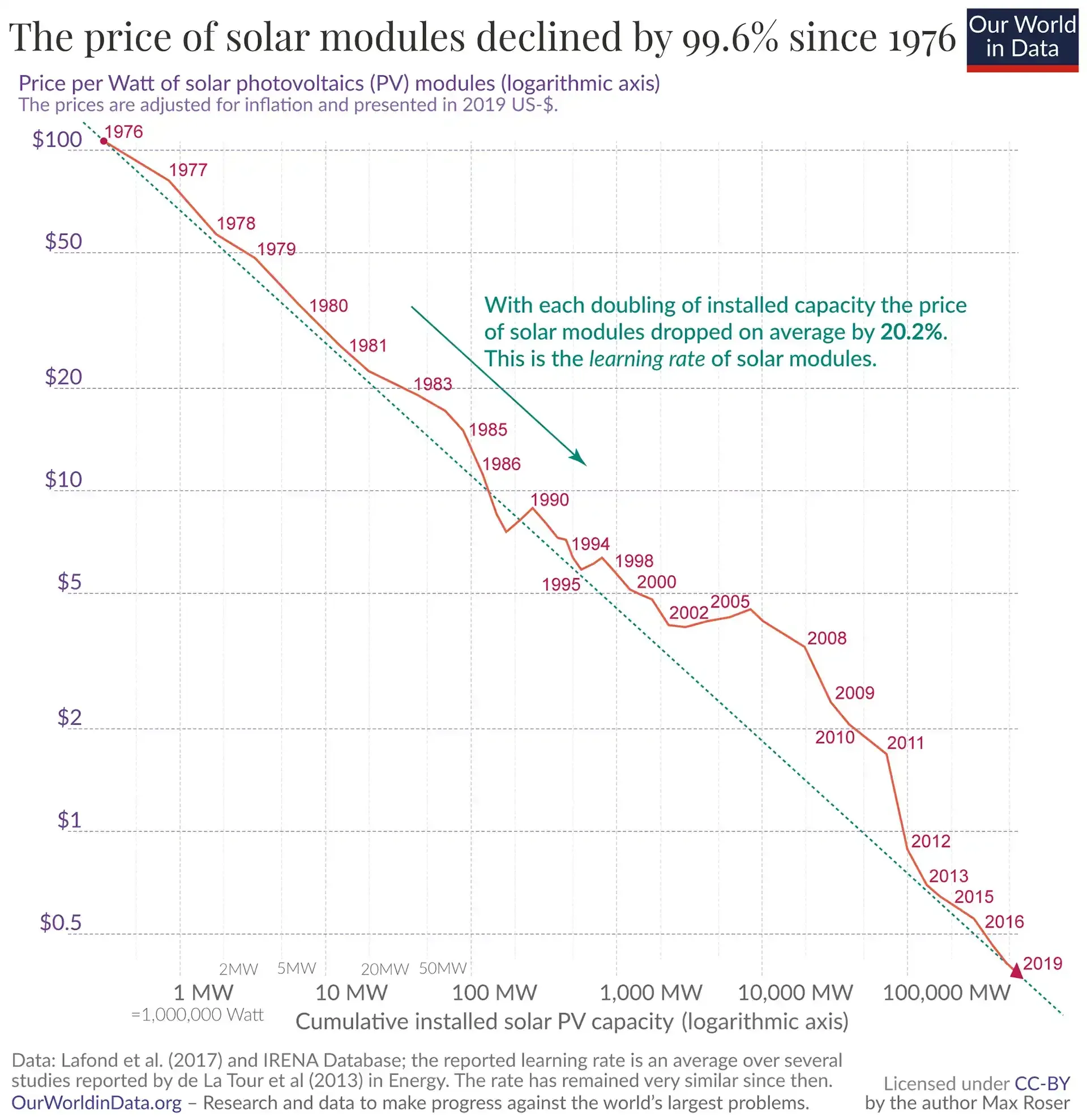

The graphic below shows Wright's Law, also known as learning rates, showing that the cost per unit decreases the more of something we produce. This one is for solar photovoltaics, and while housing is not a product in the same way, the issues are the same; a complex end-product made up of multiple parts that all interact in complex ways that can be made in a factory.

"In some ways, if we treated housing as a product, we may address the quality issues better."

For many, referring to housing as a ‘product’ is offensive, taking away the notion of 'home' and indicating housing is not considered a human right in Australia. Yet, in some ways, if we treated housing as a product, we may address the quality issues better. If we were to move to a manufacturing approach, we could embed the quality assurance that we see for solar panels. Ironically, we get a 20-year performance guarantee on a AUD$400 solar panel, yet nothing on a AUD$1million home.

Increasing the quality requirements for housing would aid in supporting the prefabrication of homes. The evidence for the higher quality of factory-made wall, roof and floor components is strong. It is easier, faster and safer to build walls in a factory setting than in a field where the weather matters. Construction waste is lower and wider efficiencies emerge from a workforce that does not travel to dispersed parts of their cities daily, packing and unpacking their tools.

This can begin to drive the demand to a level where confidence exists to invest in the infrastructure required. However, on its own, this will not suffice, as it is the boom-bust cycle that is most damaging to the industrialisation of prefabrication.

"The only counterbalance can be non-market forces."

Given this boom-bust cycle is a product of the market economy upon which we have become reliant, the only counterbalance can be non-market forces. Government and their agencies are the only ones who can fill the voids and, while the mechanics of this are more complex than the broad concept, we have done similar things before (post-GFC), so could again.

These ‘void filling’ projects need to be delivered at the highest level of the Step Code. They are the beacons to industry––the demonstration of direction of travel––the projects to be pointed at so others can say ‘like they did’. After all, the cost-curve of solar PV did not decline so rapidly because everyone waited for the next project to push the boundaries. Tomorrow never comes!

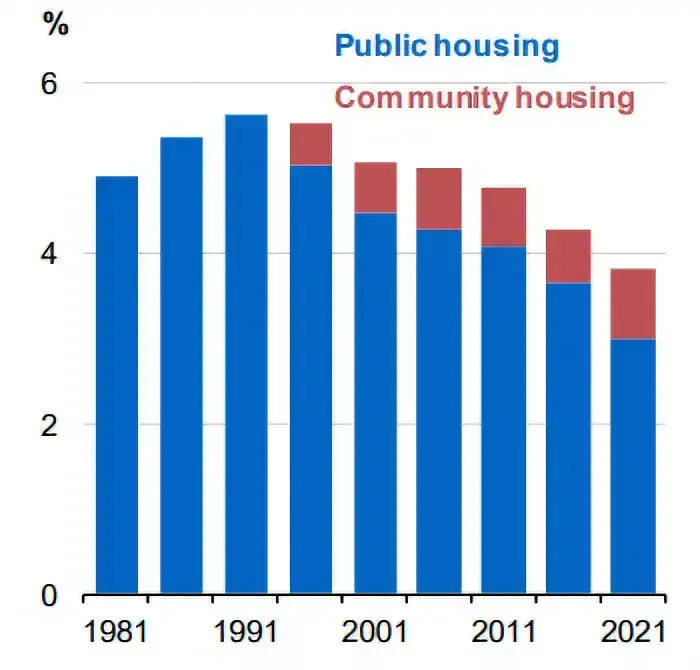

These projects will then begin to address the decline in social housing that has been underway for so long. This part of the housing system can revert to its purpose; to support those who are less able to support themselves. While the initial upside could be lower rents in the private sector and lesser competition to secure a rental, it is possible this changing demand could also drive the retrofit market, as lower quality homes struggle to rent. Obviously, a strong government policy on rental standards could achieve this too––the current moves in Victoria are a great start.

When looking around the world, it becomes apparent that building quality standards in most developed nations are noticeably higher than Australia, with New Zealand being a team mate at the rear of the pack. The standards being applied in other nations all bear a remarkable appearance to the Passivhaus Standard, although few nations have done it by directly calling it up in their codes (some, such as Scotland, have).

The Passivhaus Standard originated in Germany in the early 1990s. It is science-based and sets limits on heating and cooling energy for a building, with a focus on five key areas:

● Insulation appropriate to the climate;

● Windows, glazing and shading;

● Minimising thermal bridges;

● Air-tight construction;

● Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery.

The certification process includes post-construction verification, and it is the most reliable building standard in the world when predicted versus as-built performance is the metric of success. It is this elimination of the 'performance gap' that gives it a reputation as a quality assurance scheme, which provides confidence to developers that their new stock will deliver for the occupants.

The social housing sector, in particular, has seen a boom in passivhaus projects in both the UK and the United States in recent years. The appeal of high-quality buildings with lower operational and maintenance costs explains why these sectors come hot on the heels of the single residential market.

The competitive funding process in some US states have been awarding additional points to passivhaus projects, with Pennsylvania seeing the cost of multi-family passivhaus projects come in below that of Code-compliant ones, as they seek more cost-effective ways to deliver. The UK experience of the initial cost burden of building better has been shown to decrease rapidly as teams build their capacity. Current estimates show the cost premium at ~1%.

The interrelationships within the housing sector are diverse, complex and have evolved over time. The changes in the past decades that have seen the divergence between housing costs and ability to pay would take a similar timeframe to unwind, even if the political will did exist. Lifting the bar for quality, while simultaneously delivering additional social housing, would begin to address the supply problem while also playing a role in supporting local manufacturing, higher skilled jobs, productivity more broadly, cost-savings to the health system and improving the quality of life of those residing in social housing.

In the scheme of available options and political capital, it is as a low a bar to entry as possible.

Share This Article

Other articles you may like