What’s the story behind one of Australia’s longest-running Aboriginal community housing organisations? We speak to

Tony Gilmour who joined forces with

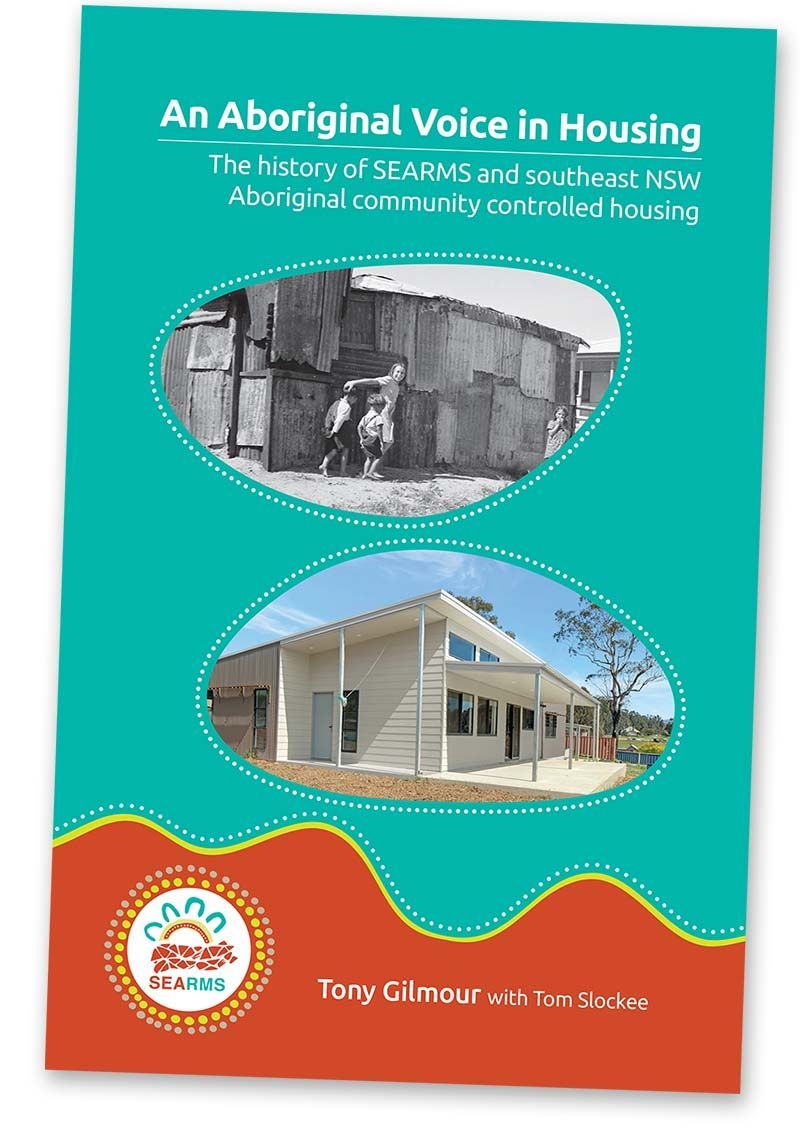

Uncle Tom Slockee to immortalise the history of SEARMS in print with the book

An Aboriginal Voice in Housing: The history of SEARMS.

"If you don't describe some of the things that can go wrong, then people will never learn."

“In a sense, what my co-author, Uncle Tom Slockee, and I both wanted was that, if you don't describe some of the things that can go wrong, then people will never learn. What tends to happen when a community organisation has problems — and nearly every community housing organisation will have some problems at some stage — it just shows that they are addressed. And maybe other people can look at it and think, well, actually from what we've read in this book, maybe we wouldn't want to go down that pathway, we could do it differently.”

“This is the old story that, if you don't talk honestly about the past, then the mistakes carry on repeating themselves. And that's been the case, particularly with Aboriginal affairs, since colonisation started.”

Scholastic rigour, accuracy and balance are essential to any historical documentation project. In this instance, Tony was confronted with many competing elements to weigh up. In the case of SEARMS, finding a starting point at which to launch from was problematic. Evidently, even though they were marking their 20th anniversary, it turned out that 2003 could be said to be a contentious starting point.

"So, how do you manage the whole pre-invasion then colonial times?"

“It turned out to be a bigger task than I thought because a lot of their antecedent organisations that coalesced in 2003 had been set up in the 1970s and 1980s. It was a rather larger history. To some extent, with any history, but particularly with Aboriginal histories, you have to go back a long time because of all the deeply ingrained issues. And so, how do you manage the whole pre-invasion then colonial times?”

In telling SEARMS’ story, Tony was forced to reassess many of the things he’d learned during his long and illustrious career in the housing sector. Even though it was charting the history of SEARMS from 2003 to 2023, he could see that a proper history of the Aboriginal community housing sector needed to go back further.

"I found out that Aboriginal community housing predated mainstream community housing by nearly 10 years."

“We'd already found another 30 years, which I don't think people were particularly aware of,” he says. “I also found out that Aboriginal community housing predated mainstream community housing by nearly 10 years. So, actually, all these community housing providers have learned from blackfellas and their history — or they should have done! — which I think is a lovely reflection.”

As well as these insights, Tony quickly learned that Aboriginal housing extended well beyond Australian capital cities too.

“I saw it as being quite an urban thing. I used to live in Redfern, and I knew about The Aboriginal Housing Company there. I was aware of housing from the Aboriginal urban activist side, and I'd written the history of Shelter New South Wales, so I knew about urban activism.”

Uncle Tom Slockee reads selected text from the book, including some traditional Aboriginal approaches to housing.

“What I hadn't realised was there was an equal amount going on in regional areas, and that it just so happened [that] the south coast of New South Wales — maybe that's because that was the area I was studying — was a hotbed of activism and leadership.”

“It's really the way that the activists who were empowered through getting free higher education, and the civil rights movement in the ‘60s into the '70s, it's those activists that were involved both in white and black activism that then were the people who took the leadership role of these organisations going forward. SEARMS didn’t just land in 2003 in Yangary Batemans Bay, and wow, that's that. They were building on the shoulders of blackfellas who'd been pushing for this for 30 or more years. There wasn't very much that happened in Aboriginal housing affairs that wasn't pushed for, and led, by Aboriginal people.”

Honouring the cultural sensitivities and use of language was something Tony was determined to try to get right, as well as addressing the optics of a whitefella writing an Aboriginal history.

“How do you refer to things?” he begins. “Well, I chose the term ‘non-Aboriginal people’. I had to agree with the organisation whether I call people ‘white’ or ‘black’, which I wouldn't like to do. The organisation doesn't use ‘First Nations’ as a term, so I didn't use that. But they also don't use ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’. So, you have to develop an agreed set of wording, which you probably wouldn't do if you're just writing the history of another mainstream community housing organisation.”

“It's not necessarily a good look that a white person's writing black history,” Tony continues. “And so, I only wrote the book on the basis that it will be jointly authored by myself and Uncle Tom Slockee who I've known for a long time, and we get on like a house on fire.”

"There are a lot of tensions and issues as to how things can be covered [in the Aboriginal sector] – even a few decades back, some of those issues are still quite raw."

“It was an interesting set-up because, obviously, I'm the one who's doing most of the writing, but he's the one who's carrying the cultural burden. And talking about things in the Aboriginal sector, there are a lot of tensions and issues as to how things can be covered – even a few decades back, some of those issues are still quite raw. We had an ongoing negotiation but, on issues to do with Aboriginality, I followed Tom. That's the only way to do it.”

The project also forced Tony to re-evaluate what he’d been taught and the academic paradigm from which it had been derived.

“Some of the non-Aboriginal academics who I'd learned my housing history from, I think had taken a bit of a top-down view of policy stuff that goes on in government departments and government agencies. A lot of that is actually reacting to what's been happening and pushed for on the ground. And so, bringing in these black voices – black leaders – I think is a really good kind of balance to what I realise now was a fairly white view of housing history, if we can say such a thing... a non-Aboriginal view of housing history.”

"I got a PhD in community housing from the University of Sydney. I realised I knew next to nothing about Aboriginal community housing. How can that be?"

“I got a PhD in community housing from the University of Sydney. I realised I knew next to nothing about Aboriginal community housing. How can that be? This book, in a sense, is going to be a leading book in its field… because it’s the only one,” he laughs.

On a serious note, Tony sees the book as a starting point for a greater awareness of Aboriginal housing: “There's been virtually nothing written about this area. If you look up mainstream community housing, it's been done to death. But Aboriginal community housing hasn't! Like why has that happened?”

“This is only a starting point. When other people come to write the next Aboriginal housing book, at least they can refer to this one and they can say that I got bits wrong, or they’ll know where the sources are, but they won't have to start almost from a blank sheet of paper, which I sometimes felt I was doing.”

The takeaway from

An Aboriginal Voice in Housing, in both Tony and Uncle Tom’s opinion, is the importance of listening. For all his research and academic rigour, it was taking the time to listen to Aboriginal elders and the wider SEARMS community, as well participating in yarning circles and other Aboriginal cultural ceremonies, that taught Tony the most.

“I spent a lot of time with Uncle Tom and Auntie Muriel, and they actually felt like my family. I was welcomed. Tom knows that my heart's in this. And so, we've caught up, had meals, had a laugh, and it just felt like being part of a family arrangement, which I don't think I'd have got writing any other organisational history.”

“The general point is that we need to listen to Aboriginal people about Aboriginal housing. We need to listen to all sorts of people about housing. So, a lot of the lessons from this are: you need to be close to, and consult with, your community, and communities have different needs and expectations.”

Tony believes this is as true for Aboriginal housing as it is across the spectrum: social housing for people on low incomes, housing for people with disabilities, housing for new migrants and people from culturally and linguistic backgrounds: “You have to be a community organisation,” he makes a point to emphasise the word ‘community’.

“One of the things Uncle Tom is very keen on is promoting further Aboriginal community-controlled organisations like SEARMS – whether it's housing co-ops or community housing organisations, Aboriginal community housing organisations. I think it’s a bigger discussion that we need.”

We need to have more SEARMS-type of organisations in Australia, full-stop, because one size does not fit all,” he states passionately. “The housing and living conditions of Aboriginal people in the south coast of New South Wales are distinctly different to Aboriginal people living in capital cities, and people living in remote areas.”

“We tend to hear a lot about Aboriginal people living in remote areas because the conditions there are the most shocking. But the approaches and solutions we need for those regional and remote areas are different to the ones we need for other areas. I feel like I've been saying that since I got involved in community housing 25 years ago, but we still need to drum that home.”

“This might seem like an Aboriginal housing book,” he concludes, “but it's got broader implications for how we run our country, how we run social services, and how we deliver things to people.”

An Aboriginal Voice in Housing: The History of SEARMS and Southeast NSW Aboriginal Community Controlled Housing

can be purchased online with all proceeds going to SEARMS.