Finance presenter and columnist

Alan Kohler traced the trajectory of Australian housing in the November 2023 edition of

The Quarterly Essay. This is an extract of that article, republished with the kind permission of the publisher and author.

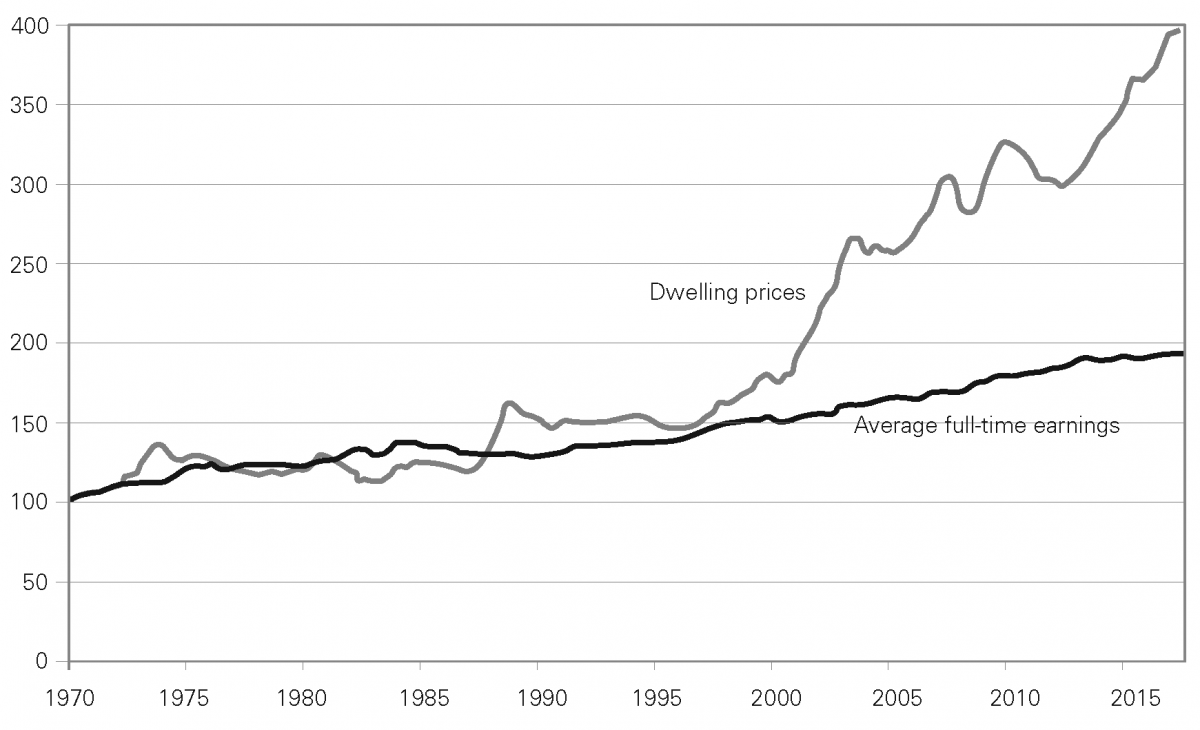

Over the past four years, our three children and their partners all bought their own first houses. They’re doing it later than we did, and much later than my parents, so they’re making better money, and both partners are working, of course, but they paid about 7.5 times each income for their houses. That was typical: in August 2023, the median Australian house price was $732,886, which was 7.4 times annualised average weekly earnings.

"My children – and all young people today – are paying more than twice the multiple of their income for a house than their parents – and their grandparents – did."

In other words, my children – and all young people today – are paying more than twice the multiple of their income for a house than their parents – and their grandparents – did, and it’s only vaguely possible because both partners work to pay it off.

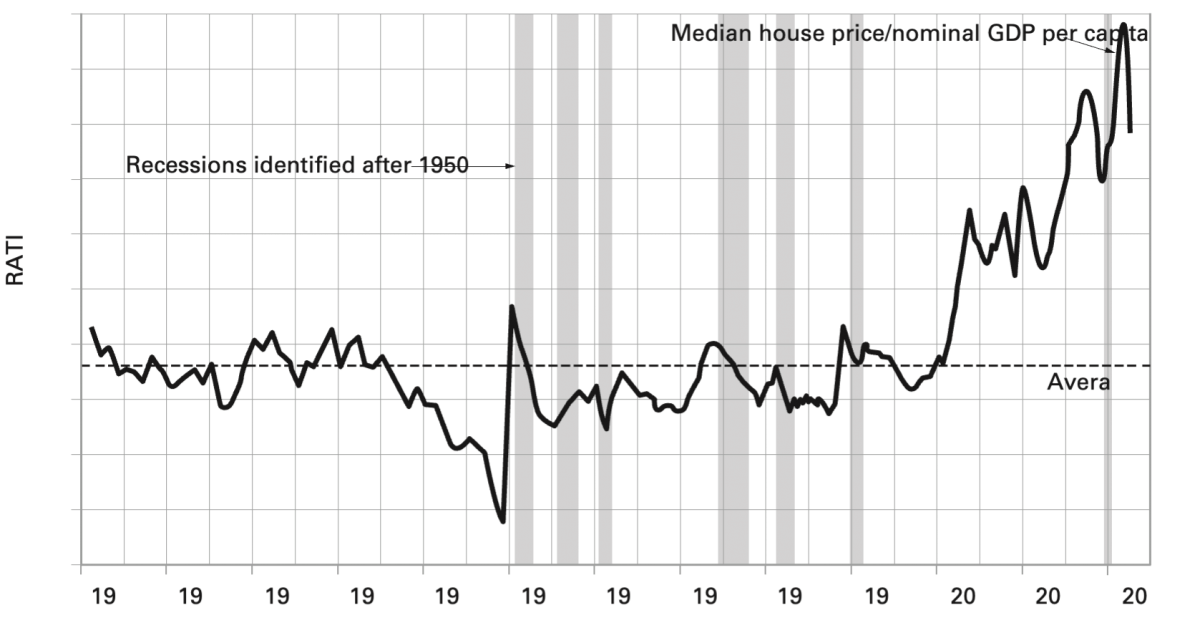

What happened, and when it happened, is evident in Figures 1 and 2.

The problem started with the new millennium.

It is impossible to overstate the significance to Australian society of what happened then. The shift that began around 2000 in the relationship between the cost of housing and both average incomes and the rest of the economy has altered everything about the way Australia operates and Australians live.

"In the Australian economy, the price of houses is not everything, but it’s almost everything."

Six per cent compound annual growth in the value of houses over the past twenty-three years versus 3 per cent annual growth in average incomes has meant that household debt has had to increase from half to twice average disposable income, and from 40 per cent of GDP to 120 per cent. This is the most important single fact about the Australian economy. The large amount of housing debt Australians carry means that interest rates have a much greater impact on their lives, and this in turn affects inflation, wages, employment and economic growth. In the Australian economy, the price of houses is not everything, but it’s almost everything, as economist Paul Krugman once said of productivity.

Land and energy are the two basic economic inputs apart from labour, but while Australia has more of both than just about any other country, we export most of the energy and price our own at global parity, so there’s no home-grown advantage there, and we crowd into a few cities and pay each other seven to eight times our salaries for land.

High-priced houses do not create wealth; they redistribute it. And the level of housing wealth is both meaningless and destructive. It’s meaningless because we can’t use the wealth to buy anything else – a yacht or a fast car. We can only buy other expensive houses: sell your house and you have to buy another one, cheaper if you’re downsizing, more expensive if you’re still growing a family. At the end of your life, your children get to use your housing wealth for their own housing, except we’re all living so much longer these days it’s usually too late to be useful. And much of this housing wealth is concentrated in Sydney, where the median house value is $1.1 million, double that of Perth and regional Australia.

It’s destructive because of the inequality that results: with so much wealth concentrated in the home, it stays with those who already own a house and within their families. For someone with little or no family housing equity behind them, it’s virtually impossible to break out of the cycle and build new wealth.

As I will argue, it will be impossible to return the price of housing to something less destructive – preferably to what it was when my parents and I bought our first houses – without purging the idea that housing is a means to create wealth as opposed to simply a place to live.

That’s easier said than done, as China’s president, Xi Jinping, has found. He’s been banging on about this for five years, saying that housing is not for speculation but for living in, but no one seems to be listening in China, and no one would be listening here either if the prime minister was saying the same thing. But anyway, he’s not.

The growth in the value of Australian land has fundamentally changed society, in two ways. First, generations of young Australians are being held back financially by the cost of shelter, especially if they live somewhere near a CBD and especially in Sydney or Melbourne; and second, the way wealth is generated has changed. Education and hard work are no longer the main determinants of how wealthy you are; now it comes down to where you live and what sort of house you inherit from your parents.

It means Australia is less of an egalitarian meritocracy. Material success is now largely a function of geography, not accomplishment. Moreover, the geographic wealth gap is being widened by climate change, as floods and bushfires make living in large parts of the country uninsurable and financially crippling, but many families have no choice but to stay where they are because those areas are low-priced and they can’t afford to move.

"The houses we live in, the places we call home and bring up our families in, have been turned into speculative investment assets by the fifty years of government policy failure."

The houses we live in, the places we call home and bring up our families in, have been turned into speculative investment assets by the fifty years of government policy failure, financialisation and greed that resulted in twenty-five years of exploding house prices. The doubling of prices as a proportion of both average income and GDP per capita has turned a house from somewhere to live while you get on with the rest of your life into the main thing, and for many people a terrible burden.

The problem of housing affordability now dominates the national consciousness and has affected the lives of everyone, dividing Australia into those who own a house and those who don’t; those whose families have housing wealth to pass on and those who don’t. And what’s more, most people now believe that the way to build wealth is to buy a house, and then another one, and another one after that, or to keep upgrading the one you live in. Or both.

A home is no longer what Australia’s longest-serving prime minister, Robert Menzies, who championed home ownership and what he called “little capitalists,” once extolled: “One of the best instincts in us is that which induces us to have one little piece of earth with a house and a garden which is ours; to which we can withdraw, in which we can be among our friends, into which no stranger may come against our will.”

There have been many fine words spoken before and after Menzies by both well-meaning and cynical politicians, but the political class as a whole has failed Australians at all levels – federal, state and local government – for a simple reason that former prime minister John Howard once put into words: “No one ever came up to me to complain about the increase in the value of their home.” Howard did more than anyone to make housing unaffordable, but at least he was honest about why.

In my view, the quiet political conspiracy identified by Howard to preserve and increase the value of houses to keep the majority of voters happy has been amplified by the banks doing the same thing to increase their profits. Australia is in the grip of a “bankocracy,” in which four banks control our access to money. Their profits, and therefore the salaries of their executives, depend on both the volume and the value of their assets growing.

The volume of their assets (that is, the number of loans) increases because Australians believe the only way to increase their wealth is to borrow 80 to 100 per cent of the value of one or more houses; and the value grows because the banks’ customers compete with each other to buy the houses and push up their prices and therefore the size of their loans. The more house prices rise, the greater the banks’ profits. As US investment guru Charlie Munger says: “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

"The way real estate works in Australia is that the federal government and banks encourage demand for it and state and local governments restrict the supply of it."

The way real estate works in Australia is that the federal government and banks encourage demand for it and state and local governments restrict the supply of it. The states restrict supply through zoning, and local councils do it by their planning decisions every day. Federal government decisions increase demand for housing in four main ways: first, through interest rates; second, with immigration; third, with tax breaks for investors and home owners; and fourth, with grants to first home buyers.

In recent years, interest rates have been the main thing determining house prices, although they are not controlled by federal politicians but rather by the independent Reserve Bank of Australia. It is a federal body, appointed by the treasurer, and it manages the economy mainly through housing. That is, interest rates regulate the cost of housing and therefore the demand for it, and to a lesser extent the supply. By reducing or increasing the cost of shelter, the RBA controls our spending on everything else, which in turn governs the level of employment and inflation.

Incidentally, the result of the thing called monetary policy is that borrowers bear the entire burden of economic adjustment. And not just all borrowers – it’s the ones who are already living on the edge. Rich borrowers are fine – they’ve got plenty left after higher repayments, so their spending doesn’t change and they don’t contribute to the economic adjustment. The spending cuts that result in slower economic growth are entirely made by those who are already struggling to make ends meet: the use of housing to regulate the economy is essentially a policy of cruelty.

As I will explain in more detail later, three main things pushed up demand for housing after 2000: a sharp lift in immigration that increased the number of people needing a place to live; capital gains tax breaks and negative gearing, which represent a $96 billion per year subsidy for buying houses; and federal first home buyer grants, which represent a $1.5 billion direct addition to house prices each year.

As for supply, in 2018, researchers at the RBA figured out that zoning restrictions raised the average price of detached houses by 73 per cent in Sydney, 69 per cent in Melbourne and 29 per cent in Brisbane. For apartments, the figures were 85 per cent in Sydney, 30 per cent in Melbourne and 26 per cent in Brisbane. Those are astonishing numbers, and that’s without including the effect of local government planning decisions, which are, by definition, haphazard and unquantifiable but mostly aimed at keeping local councillors in a job by keeping the existing residents happy by making sure they don’t let in too many new ones.

As Figure 3 shows, house prices started trending higher for the first time after World War II, but up to the turn of the millennium they were more or less keeping pace with incomes and the size of the economy.

At the same time as everybody was worrying about the world’s computers grinding to a halt with Y2K, there was a collision between demand and supply and house prices started to depart from the rest of the economy, and from our incomes. What happened in the year 2000? Well, that’s what this Quarterly Essay is about; as I’ll explain, the nitro of a surge in demand around that time mixed with the existing glycerine of restricted supply to create an explosion that has blown up the Australia that our parents knew.

And each of those things was almost entirely due to government policies, either the unintended consequences of misguided ideas or deliberate policies designed to preserve the wealth of the majority of voters – that is, those who own a house. If governments caused the problem, can governments fix it? Theoretically yes, but it’s politically easier to make an asset worth more than to make it worth less. As I’ll explain in the final chapter, actually doing something about housing affordability would require courage, Minister.

Quarterly Essay is offering readers of HousingWORKS a discount of $3 on RRP with free shipping within Australia using promo codes - HW3 (discount code), FREESHIP (shipping code) - at

www.quarterlyessay.com

This is an extract from Alan Kohler's Quarterly Essay The Great Divide: Australia's Housing Mess and How to Fix It.