Some of the key hopes that many held over the last 50 years have not been realised, such as the deepening of democracy and the intergenerational progress of wellbeing and safety. In response, protest actions that occupy streets, properties and spaces are increasing.

Grassroots activism has overtaken political and civil advocacy on geopolitical issues such as climate change and modern colonialism. Now housing has become a dominant issue for younger Australians, as a political cause with personal effects.

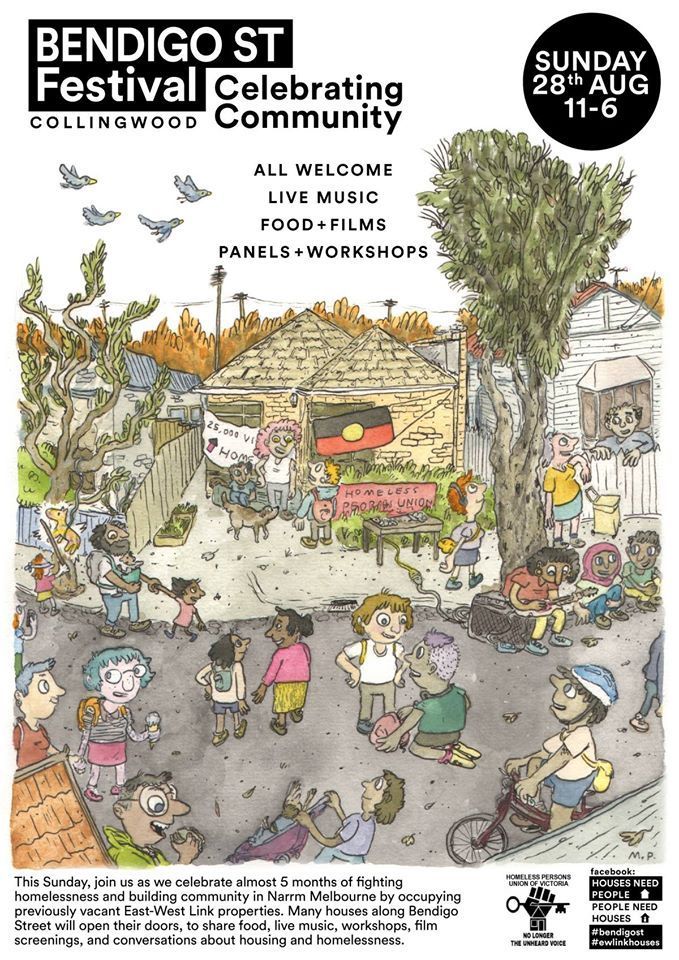

There is a lot of housing activism happening right now

The current housing crisis is not the first one that Australia has experienced, and neither is activism as the response. The immediate years after World War Two saw many instances of squatting and protest in reaction to the severe shortage of housing. Elsie, the first women’s refuge in Australia, was founded in a squatted council house in Glebe in 1975.

Recently, we have seen campaigns in Sydney and Melbourne with significant involvement of residents against the sell-off or redevelopment of public housing. We have also seen the rise of renter activism with RAHU (Renters and Housing Union) and other volunteer-based groups doing everything from organising information and rights awareness nights for low-income renters to picketing real estate agents.

Notably, there have been social-media-led actions, with the most well-known of these being Jordan Van den Berg, or ‘Purple Pingers.’ In early 2024, Van den Berg started to gain media attention for his encouragement for people to name (and shame) properties that have been left empty. Further to this, there was a suggestion these homes might be occupied by those who were in housing need among his audience. A flurry of media articles and talkback discussion about the legality of squatting and the broader issue of regulation of empty homes followed (see HousingWORKS article on 'meanwhile use' housing).